The Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli

This popular basilica was built over the temple Juno Moneta (home of the early Roman mint, hence the English word "money"). The appellative "Ara Coeli" (or altar of the heavens) is due to the Marian apparition that happened to the emperor Ottaviano.

We know for a fact that by 574 the site housed a monastery of Byzantine monks (in the 6th century Rome was governed by Byzantine exarchs). From the 9th to the 13th centuries the church and monastery belonged to the Benedictines, and in 1249 a papal bull from Innocenzo IV ceded the complex to the Order of Friars Minor. The Franciscan friars renovated the church according to the Roman-Gothic architectural style and reconsecrated it in 1291.

Down through the ages, the Capitoline church has remained faithful to its illustrious classical past. Petrarch, the 13th-century poet who revived interest in the ancient world, received the laurel wreath nearby. And it was Cola di Rienzo, the self-proclaimed Tribune of the Roman People, aspiring to restore Rome to its imperial glory, who first ascended the Aracoeli staircase after it had been built in 1348 by the vote of the Roman people (in thanks for deliverance from the Black Death). Cola di Rienzo was later lynched as a demagogue in the place where his statue now stands at the bottom of the Aracoeli ramp.

Like all Roman churches, Santa Maria in Aracoeli is a repository of art treasures from every period. A sad-faced Byzantine Madonna gazes out from the Baroque altar. Although most art historians date the Madonna to the twelfth century, an Aracoeli legend claims that the image, painted on a piece of beech wood, was carried by Pope St Gregory the Great in the year 594 through the streets of Rome, and brought about the city's deliverance from a terrible plague. The Aracoeli Madonna thus rivals Santa Maria Maggiore's for the title of Sales Populi Romani (Salvation of the Roman People).

The 13th-century sculptor Arnolfo da Cambio executed a Madonna and a sepulchral monument in the transverse nave, and further down on the same side we find a tomb designed by Michelangelo for a family friend, Cecchino Bracci. Towards the sacristy, a tall and slender - and very modern - bronze statue of St Helena, created by a Franciscan artist in 1972, stands over the shrine containing the saint's relics. Across from St. Helena, a 15th-century portrait of Queen Catherine of Bosnia looks out mournfully from her upright tombstone. Although we have no knowledge of the queen's concerns of five centuries ago, her expression seems especially fitting today.

You can find a tombstone signed by Donatello, an especially tender 15th-century Sienese Madonna, "Refugium Peccatorum" (Madonna Refuge of Sinners) on a column, and other works attributed to Pietro Cavallini, Benozzo Gozzoli, and Giulio Romano.

Probably the church's greatest treasure, Pinturicchio's fifteenth-century series of frescoes on the life of Saint Bernardine of Siena, can be seen in the first chapel on the right. The glowing colors and serene perspective of these early Renaissance paintings make them some of the most beautiful in Rome.

Santa Maria in Aracoeli boasts Rome's best-loved Christmas ritual. Every Christmas Eve the Aracoeli's ramp is lit up by candles and thronged by the Roman populace. Leather-sandalled bagpipers, in the tradition of mountaineer "pifferari" of days gone by, play Christmas music before the church door, and inside, chandeliers and tapers blaze in preparation for the ceremony.

At midnight, the Aracoeli's greatest treasure, a wooden statue is of the child Jesus (said to have been carved from an olive tree in the Garden of Gethsemene) is brought from his private chapel next to the sacristy to a ceremonial Baroque throne before the high altar, over the Vigil Mass. Upon intonation of the "Gloria," the veil is taken away and the statue is paraded to a Nativity Crib in the left side nave. Here, from his perch on the wooden manger, the chubby-faced Santo Bambino, covered in jewels from his crown to his little slippers, surveys the Christmas scene and receives tributes from the children of Rome. Mothers encourage their children to enter a temporary wooden pulpit across from the Presepio, where prayers, poems or requests are recited before the doll-like image. The Santo Bambino remains in his place of honor until Epiphany, when he is taken in procession to the top of the Aracoeli's steep staircase for a benediction of the city and its people, and then returned (after being exposed for an entire day for Romans to give the traditional Epiphany kiss) to his personal chapel at the back of the church. The diminutive Santo Bambino has every reason to exult. Perhaps nowhere else in Rome but this most ancient and seemingly highest hill of the Aracoeli does one feel so surely the triumph of Christianity over pagan Rome, and the victory of the spiritual over temporal power in Christianity's capital.

Address in Rome:

Piazza Campidoglio, 55.

Have you seen our self-catering apartments in Rome?

Amalfi Coast

Amalfi Coast Sorrento Coast

Sorrento Coast Tuscany

Tuscany Cilento National Park

Cilento National Park Lake Como

Lake Como Rome and Latium

Rome and Latium Umbria

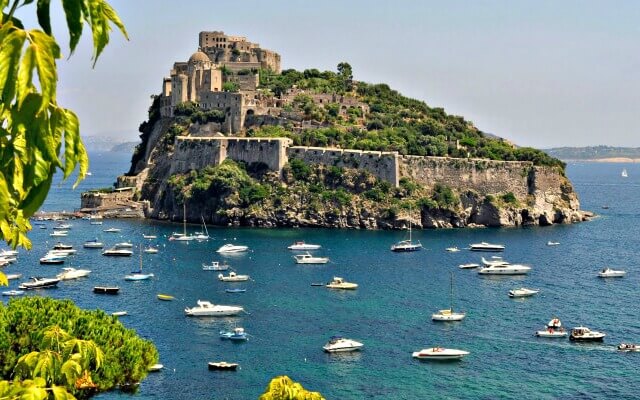

Umbria Capri and Ischia

Capri and Ischia Venice

Venice Puglia (Apulia)

Puglia (Apulia) Liguria

Liguria Sicily

Sicily Lake Maggiore

Lake Maggiore Lombardy

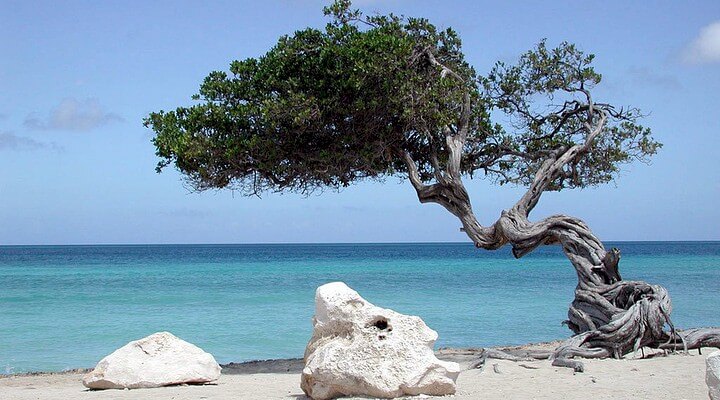

Lombardy Sardinia

Sardinia Lake Garda

Lake Garda Abruzzo and Marche

Abruzzo and Marche Calabria

Calabria